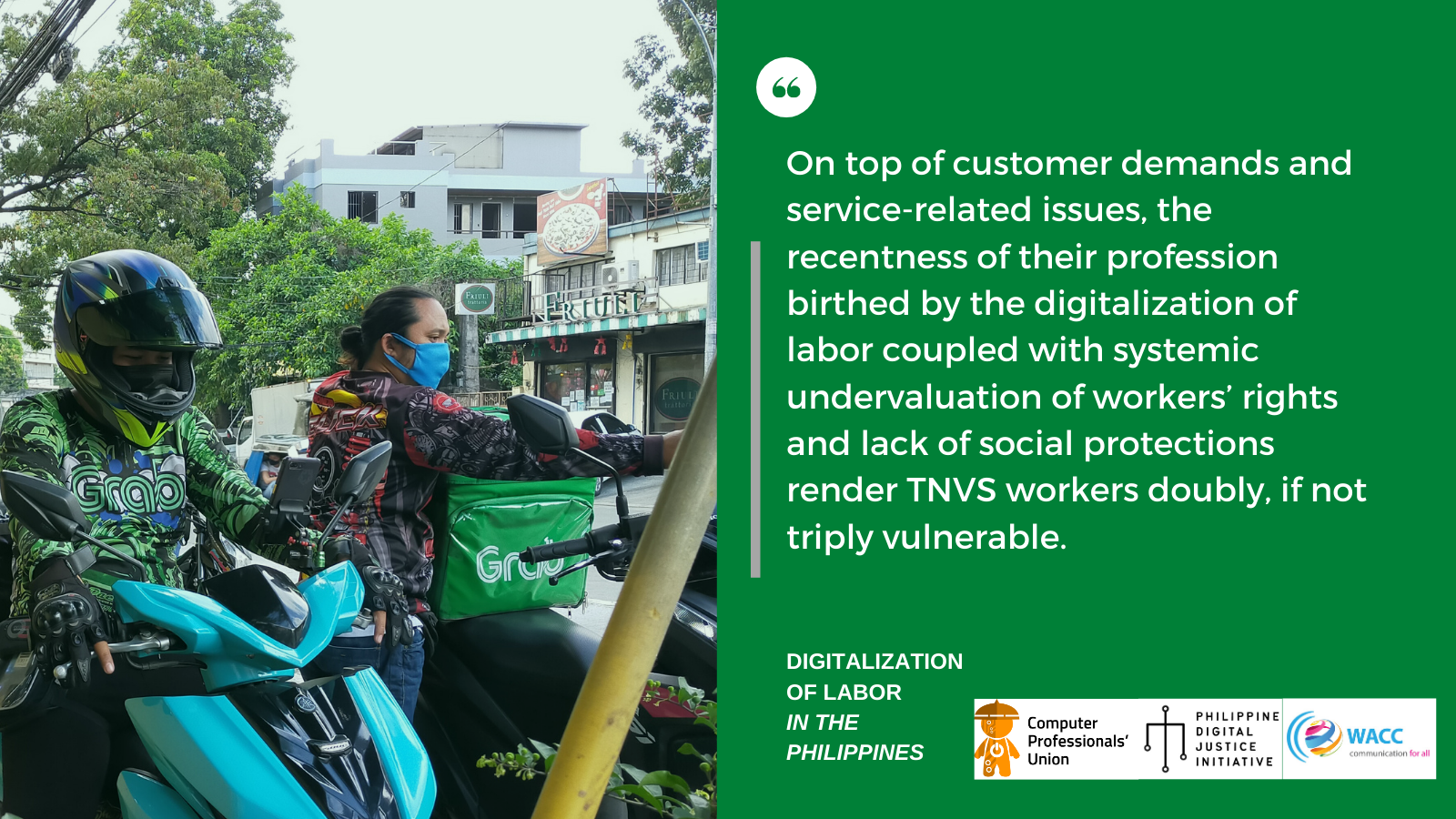

With the digitalization of our daily life and the economy in general, Transport Network Vehicle Services (TNVS) such as Grab, Foodpanda, Lalamove, Angkas and other similar companies have become a common sight for the past few years and have proven to be an essential companion in the daily lives of most of us, especially during the early months of the pandemic.

Albeit new compared to other essential professions, their importance in delivering not only food and beverages but convenience and comfort, has been continuously being proven as days go by. Still, the cases of FoodPanda protest in DOLE and OWTO in LTFRB show that despite being a new building block in a digitalizing society (at least in the urbanized areas) they experience issues in labor that stems from their recentness in the economy. With that, this article will provide a snapshot of the current state of the GrabFood couriers currently face in their jobs. Sourced from GrabFood courier themselves, this includes the perks of working under a TNC (Transport Network Company), protruding problems they experience during work, as well as their suggested solution to these problems.

Most of the GrabFood couriers interviewed mentioned two main reasons why they like working in Grab than their previous blue-collar jobs: the flexibility in working hours and the chance of earning above-minimum wages. The first one is advantageous for both part-time–including working students—and full-time employees, as they can still manage their academics and pursue recreational activities such as playing video games, watching K-drama, or spending time with their family while earning a decent amount of salary. The second one is also favorable to GrabFood couriers than their previous jobs because although there are days wherein the bookings they receive are low (earning only 200 to 300 pesos for 9 to 12 hours of work), the chances of receiving more booking that can give them 900 to 1,500 pesos for a day of grind is a much more preferable trade than working on their previous blue-collar jobs in factory and security.

But not all things are composed of bright colors—and for the GrabFood couriers, there are times when the negative aspect of work outweighs the advantages of their profession. Some of the usual problems that GrabFood courier encounters include fake bookings (the scams usually published in news) and uncooperativeness from customers who provide inaccurate or incomplete details about their orders or locations. Although Grab was able to solve this issue by giving reimbursements to couriers that encountered such incidents, couriers voiced-out that requiring face-recognition in customers and banning the linked mobile number of those that committed fraud would help them minimize such cases from happening in the future.

Although the aforementioned problems are only minors and bearable for most couriers, there are systematic problems under GrabFood that are more pressing for workers: these are the benefits and medical assistance, unfair booking system, and “territoriality” of GrabFood application.

Although some of the couriers do not mind handling their benefits on their own (this includes SSS, PhilHealth, and Pag-Ibig), the majority of them prefer that the company would take the lead in supervising the benefits given the fact that they are their hired workers and could give the workers spare time to do other activities. Besides, minor accidents should be similarly covered by GrabFood that it covers related expenses in severe accidents (including the death of workers during operation), as the workers voiced-out that they are always at risk on road every time they start their engine or kick their pedals every time they deliver. A wider safety net would go a long way, said the couriers.

The “territoriality” feature of GrabFood, wherein couriers who have not opened their booking in an area for more than two weeks receive little or no booking at all, is what the GrabFood courier under the alias “Jonel” wants to be addressed or removed, as this prevents drivers from quickly moving to a specific area that has a surplus of booking and earning more for their day of work while the demands in their “territory” are minimal.

As mentioned above, the couriers see no problem with the uncertainty of their daily wages, as they understand that there are times when the demand for their service is low. However, the majority of the couriers interviewed feel that the “random” booking system of GrabFood is not random at all and seems to treat them unfairly, leaving some couriers with little to no earnings at all while others receive plenty of booking. According to them, the booking system favors the couriers that have had a continuous booking from their previous working days, causing a domino effect that is beneficial to those that had many bookings already but detrimental to those that did not get lucky. Seeing and experiencing the dire effects of this unequal booking system, there was a group of GrabFood couriers who tried to solve this problem by creating a consensus among them wherein if a courier reached at least 800 pesos for one working day, they should decline the booking so other couriers could receive this instead. Although this mitigates the chance of earning more than a thousand peso, the couriers agreed to establish this system. Unfortunately, the system was scrapped as there were couriers who did not abide by the agreement. Until there is no clearer or better system, couriers will remain to be at the mercy of GrabFood’s random booking system and continue to feel uncertainty and unfairness in their work.

The TNVS, albeit a new type of job, is vital in the economy and has proven its vital role during the early months of pandemic lockdown until today. Despite their importance to the economy, TNVS experience different work-related difficulties. On top of customer demands and service-related issues, the recentness of their profession birthed by the digitalization of labor coupled with systemic undervaluation of workers’ rights and lack of social protections render TNVS workers doubly, if not triply vulnerable. As the advancement of technology permeates and affects our daily lives faster than we recognize it, we should strive to understand and provide a solution to problems that come with it. Otherwise, our own making may outpace us in manners unimaginable.